(ERNEST HILBERT) TOLSTOY, Leo. War and Peace, translated by Aylmer and Louise Maude. San Diego: Canterbury Classics / Baker and Taylor, 2011. Stout octavo, hardcover. $24.95. ISBN-10: 1607103109

Introduction

Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace is one of the most famous novels of all time, and justly so. It is certainly one of the longest. Its title, emblematic of the grand sweep of the lives chronicled within, is recognizable even to those who will never read it. It is celebrated for its dizzying cast of characters, its shrewd examinations of the demands history places on individual human lives, and, of course, its exhilarating story lines. It features nearly 600 characters, some of them authentic historical figures, others invented by their author. It is known for its narrative sweep as well its length, more than 1,000 pages in most editions. It is unlikely that Tolstoy could have successfully forged his masterpiece in a less capacious form. It is not, however, a complex novel. In fact, its straightforward nature is part of its greatness. As the narrator of the book assures us, “There is no greatness where simplicity, goodness, and truth are absent.” Alongside Anna Karenina (1873–77), War and Peace is Tolstoy’s greatest accomplishment, as well known today as it was upon publication in 1869.

Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace is one of the most famous novels of all time, and justly so. It is certainly one of the longest. Its title, emblematic of the grand sweep of the lives chronicled within, is recognizable even to those who will never read it. It is celebrated for its dizzying cast of characters, its shrewd examinations of the demands history places on individual human lives, and, of course, its exhilarating story lines. It features nearly 600 characters, some of them authentic historical figures, others invented by their author. It is known for its narrative sweep as well its length, more than 1,000 pages in most editions. It is unlikely that Tolstoy could have successfully forged his masterpiece in a less capacious form. It is not, however, a complex novel. In fact, its straightforward nature is part of its greatness. As the narrator of the book assures us, “There is no greatness where simplicity, goodness, and truth are absent.” Alongside Anna Karenina (1873–77), War and Peace is Tolstoy’s greatest accomplishment, as well known today as it was upon publication in 1869.

The novel consists of a series of interlinked family dramas set against the spectacular background of Napoleon’s Europe, most notably the 1805 Battle of Austerlitz and the French emperor’s 1812 invasion of Russia, which culminated in the ferocious Battle of Borodino, the capture and incineration of Moscow, and the bleak, disastrous retreat of the French army in Russian winter. Although it may be read as a realistic, historical novel, War and Peace is much more. Tolstoy chose to blend history, philosophy, and fiction in an unprecedented manner, hoping to transcend existing literary conventions. He wrote, somewhat evasively, of War and Peace that it is “not a novel, even less is it a poem, and still less an historical chronicle.” One of Tolstoy’s foremost biographers, A. N. Wilson, suggests that what Tolstoy probably meant by this was simply that readers are “not merely to lap it up in the same spirit in which they might read installments of David Copperfield or Crime and Punishment . . . Tolstoy knew, just as Dante and Shakespeare must have known in their day, that he had produced a masterpiece which it would be completely unhelpful to compare with an ordinary serial novel.” Tolstoy sought to defy all expectations, to shock the reading public with something genuinely new. It is not hard to mention Tolstoy in the same breath as the likes of Dante and Shakespeare, Cervantes and Voltaire. War and Peace, as immense and powerful as Russia itself, places him safely in the first rank of world authors. What he created, according to Wilson, is nothing less than an “epic, a retelling of national myth, which is comparable, in Russian terms, with Homer.”

The novel consists of a series of interlinked family dramas set against the spectacular background of Napoleon’s Europe, most notably the 1805 Battle of Austerlitz and the French emperor’s 1812 invasion of Russia, which culminated in the ferocious Battle of Borodino, the capture and incineration of Moscow, and the bleak, disastrous retreat of the French army in Russian winter. Although it may be read as a realistic, historical novel, War and Peace is much more. Tolstoy chose to blend history, philosophy, and fiction in an unprecedented manner, hoping to transcend existing literary conventions. He wrote, somewhat evasively, of War and Peace that it is “not a novel, even less is it a poem, and still less an historical chronicle.” One of Tolstoy’s foremost biographers, A. N. Wilson, suggests that what Tolstoy probably meant by this was simply that readers are “not merely to lap it up in the same spirit in which they might read installments of David Copperfield or Crime and Punishment . . . Tolstoy knew, just as Dante and Shakespeare must have known in their day, that he had produced a masterpiece which it would be completely unhelpful to compare with an ordinary serial novel.” Tolstoy sought to defy all expectations, to shock the reading public with something genuinely new. It is not hard to mention Tolstoy in the same breath as the likes of Dante and Shakespeare, Cervantes and Voltaire. War and Peace, as immense and powerful as Russia itself, places him safely in the first rank of world authors. What he created, according to Wilson, is nothing less than an “epic, a retelling of national myth, which is comparable, in Russian terms, with Homer.”

Biography

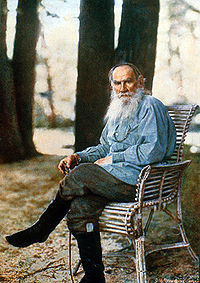

Leo Tolstoy was born in 1828 to a well-respected aristocratic Russian family. In 1862 he married Sophia Anreevna Bers, and she joined him at his remote, rugged, and somewhat neglected country estate. Wilson tells us this was “quite frightening for an eighteen-year-old Europeanized city girl” who was used to the “jolly people who streamed in and out of her mother’s Moscow drawing room.” Nevertheless, she adapted to life in the country. She bore thirteen children, five of whom died in childhood. The couple worked closely together, Sophia acting as editor and proofreader for War and Peace among other works. Although their early marriage is thought to have been reasonably happy, Tolstoy’s overbearing personality and increasingly adamant radicalism—which included efforts to renounce his inherited wealth—tried Sophia’s patience and wore heavily on the couple’s later married life. Tolstoy lived until 1910, when he succumbed to pneumonia in a train station at the age of eighty-two, not long after surrendering all worldly possessions and striking out for a life as a wandering ascetic.

Tolstoy has always inspired great respect and even adulation from other authors. In his own day, he was hailed by the likes of Gustave Flaubert, Anton Chekhov (who felt Tolstoy’s authority to be “enormous”), and Fyodor Dostoyevsky, who considered him to be the greatest living novelist. After Tolstoy’s death, famous writers—including Virginia Woolf, Thomas Mann, James Joyce, Marcel Proust, and William Faulkner—continued to heap laurels on his accomplishments. G. K. Chesterton emphasized Tolstoy’s “immense genius.” American novelist Ernest Hemingway, who imagined himself sparring with famous novelists, confessed, “I’m not going to get into the ring with Tolstoy.” Maxim Gorky went so far as to declare, “Tolstoy is a whole world.”

His literary reputation aside, Tolstoy served as a crucial influence on political thinkers and reformers. He became something of a prophet to his followers. His pacifism, based in both his Christianity—particularly his sympathies with the Sermon on the Mount—and his own firsthand impressions of the savagery of warfare, eventually led him down the path of philosophical anarchism. His writings on Christianity and nonviolent resistance had far-reaching consequences after his book The Kingdom of God Is Within You came to the attention of a young Mohandas Gandhi, who would put Tolstoy’s ideas of nonviolent resistance to great use (the two would go on to correspond). Alexander Fodor wrote, “We know that [Tolstoy’s] pacificism, his advocacy of passive resistance to evil through nonviolent means, has had incalculable influence on pacificist movements in general and on the philosophical and social views and programs of Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King, and Cesar Chavez.”

The Book

Tolstoy began to write War and Peace in 1862, the year he married Sophia. In fact, it is very possible that without his wife’s patience and help his masterpiece would not have found its final shape. Alexandra Popoff considers her as “multifaceted as her genius husband.” Astonishingly, Sophia copied out no fewer than seven versions of the novel by hand before its first publication, in Russian, in 1869 as Voyna i mir, a title Tolstoy borrowed from French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s La Guerre et la Paix. However, Wilson explains that she was no “mere copyist”:

At every stage . . . she advised and commented upon the work, giving intelligent reflections not only upon the content but also its manner of presentation and publication . . . given Tolstoy’s habits of self-doubt and indolence, it is improbable whether, without his wife’s help and guidance, the work would ever have reached a conclusion.

Serfdom—the feudal custom by which peasants were assigned for life to a plot of land and essentially owned by a landholder—was abolished in Russia only in 1861, a year before Tolstoy began work on his great novel. Swept up in the general movement toward social reform, Tolstoy attempted to pass control of his own estate, Yasnaya Polyana, to his former serfs. Like so many aspects of Tolstoy’s life, this ill-fated undertaking finds its way into the novel when Pierre Bezukhov, after receiving a vast inheritance, wonders of his new wealth, “How have you used it? What have you done for your neighbor? Have you ever thought of your tens of thousands of slaves? Have you helped them physically and morally?” Pierre’s naïveté and slapdash scuttle to reform his estates guarantee a disastrous outcome, in which “nine-tenths of the peasants in the villages were in a state of the greatest poverty,” a worse position than they had endured before Pierre’s idealistic reforms. Likewise, Tolstoy’s “experiment to let the peasants run the farm themselves was a complete failure,” according to Wilson. Tolstoy worked hard to identify with the peasants, donning the humble garments he was so often photographed wearing, but his attempts at animal husbandry and farming failed dismally. His talents lay elsewhere.

War and Peace guides the reader through a vast landscape of human interactions and emotions, including comic commotions, deathbed watches, youthful flirtations, religious inspirations, political disillusions, and moments of terrific joy, peaceful contentment, soul-wrenching terror, and crushing disappointment. While ranging cinematically from the battlefield to the drawing room, Tolstoy almost magically fixes the lens of the story to capture the point of view of a particular character before jumping to the next, sometimes hovering majestically over an immense historical event, such as the occupation of Moscow, before zeroing down to describe the thoughts, fears, and aspirations of one of many hundreds or thousands gathered there.

Tolstoy makes use of several historical figures, such as Tsar Alexander I, who ascended to the throne at the age of twenty-four, and the self-made (and self-crowned—he was born a Corsican commoner) emperor Napoleon Bonaparte—two of the novel’s questionably “great men,” surrounded by entourages, with seemingly infinite resources at their disposal (though for Tolstoy they are as subject to fate as any others). He also sketches colorful invented characters such as the lively Tikhon Shtcherbatov, a resourceful and sadistic peasant scout taken on by a partisan force harrying the retreating French army in the fateful winter of 1812. The carefully portrayed aristocratic characters that assume most of the novel’s attention are conjured from Tolstoy’s own family and social milieu. He drew from his diary, historical records, and visits to battlefields. In so doing, he gained powerful insights into human behavior. British political theorist and essayist Isaiah Berlin wrote that “no one has ever excelled Tolstoy in expressing the specific flavor, the exact quality of a feeling—the degree of its ‘oscillation,’ the ebb and flow, the minute movements . . . the inner and outer texture and ‘feel’ of a look, a thought, a pang of sentiment, no less than of a specific situation, of an entire period, of the lives of individuals, families, communities, entire nations.” It is impossible to summarize the action of the lengthy novel, but it is possible to discuss the stimulating authenticity Tolstoy brings to its cast.

The novel’s central characters belong to a handful of aristocratic families: the Rostovs, Bezukhovs, Bolkonskys, Drubetskoys, and Kuragins. Their lives, often tumultuous and dramatic even in times of peace and prosperity, are thoroughly swept up by larger historical currents as sons enlist to fight Napoleon, mothers and the aged are forced to flee estates, and all of Russia struggles for survival against the French invaders. Fortunes are gained and lost through marriages and inheritances. Lovers are torn apart and brought together again. Characters that appear unlikely pairs find wedded bliss after tremendous hardships. The complex symmetries and subtle harmonies of the many plot lines are breathtaking.

1805

Nearly all of the novel’s action takes place in two decisive years, 1805 and 1812, when Napoleon’s eastward advances disturb the characters’ peaceful lives. The War of the Third Coalition (1803–6) brought Napoleon into conflict with several European states, including Austria and Russia, who allied against his imperial aspirations. Napoleon first set his sights across the English Channel, but Great Britain’s traditional sovereignty over the seas became indisputable after Admiral Horatio Nelson’s victory at Trafalgar in October 1805. This setback forced Napoleon to direct his attention to continental Europe. France’s Grande Armée made short work of an Austrian army at the Battle of Ulm, and Napoleon pressed on to capture the Austrian capital of Vienna. The campaign reached its climax in the Battle of Austerlitz, also known as the Battle of the Three Emperors: Russia’s Tsar Alexander I, Austria’s Francis II, and Napoleon himself.

Nearly all of the novel’s action takes place in two decisive years, 1805 and 1812, when Napoleon’s eastward advances disturb the characters’ peaceful lives. The War of the Third Coalition (1803–6) brought Napoleon into conflict with several European states, including Austria and Russia, who allied against his imperial aspirations. Napoleon first set his sights across the English Channel, but Great Britain’s traditional sovereignty over the seas became indisputable after Admiral Horatio Nelson’s victory at Trafalgar in October 1805. This setback forced Napoleon to direct his attention to continental Europe. France’s Grande Armée made short work of an Austrian army at the Battle of Ulm, and Napoleon pressed on to capture the Austrian capital of Vienna. The campaign reached its climax in the Battle of Austerlitz, also known as the Battle of the Three Emperors: Russia’s Tsar Alexander I, Austria’s Francis II, and Napoleon himself.

Several of the novel’s principal characters, including Prince Andrew, find themselves catapulted into battle at Schön Graben, a delaying action at which the Russian forces capably slow Napoleon’s progress, and then at Austerlitz, where the combined Russian and Austrian forces are outwitted and destroyed by Napoleon in one of the most decisive battles in European history. Tolstoy draws on his own memories of battle during the Crimean War, when he served as an artillery officer from 1854 to 1855 (he published his accounts in 1855 in Sevastopol Sketches), to lend an undeniable realism to the novel’s battle scenes. He is particularly adept at bringing to life set-piece battles viewed at eye level, when confusion, desperation, and miscommunication hold sway. For instance, the stark contrast between war and peace is crystallized in a gruesome scene played out during the frantic retreat across the Augesd Dam after the Russian Imperial Army’s humiliating defeat on the Pratzen Heights at Austerlitz:

On the narrow Augesd Dam where for so many years the old miller had been accustomed to sit in his tasseled cap peacefully angling, while his grandson, with shirt sleeves rolled up, handled the floundering silvery fish in the watering can, on that dam over which for so many years Moravians in shaggy caps and blue jackets had peacefully driven their two-horse carts loaded with wheat and had returned dusty with flour whitening their carts—on that narrow dam amid the wagons and the cannon, under the horses’ hoofs and between the wagon wheels, men disfigured by fear of death now crowded together, crushing one another, dying, stepping over the dying and killing one another, only to move on a few steps and be killed themselves in the same way.

At Austerlitz, Prince Andrew, once hungry for glory—dazzled by the martial pageantry of standards and uniforms, seduced by the aura of power that surrounds the generals—is struck a near-fatal head wound by a musket ball. He is lifted from the battlefield by victorious French soldiers, and, on the brink of death, is scrutinized by none other than the emperor Napoleon, who remarks “He’s very young to come to meddle with us.” The scales fall from Prince Andrew’s eyes. Though only hours before he esteemed Napoleon as a great man, he suddenly sees him only as a petty, strutting, self-satisfied creature:

So insignificant at that moment seemed to him all the interests that engrossed Napoleon . . . Looking into Napoleon’s eyes Prince Andrew thought of the insignificance of greatness, the unimportance of life which no one could understand, and the still greater unimportance of death, the meaning of which no one alive could understand or explain.

1812

The second important year in the novel is 1812, when Napoleon, with a massive coalition army of 600,000 soldiers at his back, crosses the frontier into Russia. He has quarreled with Tsar Alexander. He plans to exact revenge for Russia’s refusal to adhere to his Continental Blockade of Great Britain, a power that remained always a thorn in the French emperor’s side. At the start of the year, Napoleon confidently controls nearly all of Europe either directly or through treaties that greatly favored France. Despite ongoing troubles in Spain and the sneer of the British, it seems that Napoleon cannot be defied. After a handful of early victories in Russia, and what can only be called a bloody draw at the Battle of Borodino, Napoleon succeeds in capturing Moscow itself, but it proves to be a hollow victory when the city begins to burn uncontrollably and Napoleon’s exhausted army is obliged to undertake a freezing retreat, during which it is gnawed at by Cossacks and partisans, slowly dissolved by starvation and disease, and frozen by the Russian winter. By year’s end, Napoleon’s military might is reduced to a slender fraction of its former strength, and his empire is, for all intents and purposes, doomed.

The second important year in the novel is 1812, when Napoleon, with a massive coalition army of 600,000 soldiers at his back, crosses the frontier into Russia. He has quarreled with Tsar Alexander. He plans to exact revenge for Russia’s refusal to adhere to his Continental Blockade of Great Britain, a power that remained always a thorn in the French emperor’s side. At the start of the year, Napoleon confidently controls nearly all of Europe either directly or through treaties that greatly favored France. Despite ongoing troubles in Spain and the sneer of the British, it seems that Napoleon cannot be defied. After a handful of early victories in Russia, and what can only be called a bloody draw at the Battle of Borodino, Napoleon succeeds in capturing Moscow itself, but it proves to be a hollow victory when the city begins to burn uncontrollably and Napoleon’s exhausted army is obliged to undertake a freezing retreat, during which it is gnawed at by Cossacks and partisans, slowly dissolved by starvation and disease, and frozen by the Russian winter. By year’s end, Napoleon’s military might is reduced to a slender fraction of its former strength, and his empire is, for all intents and purposes, doomed.

War

Tolstoy is famous for his powerful evocations of battle. His descriptions take the reader from a bird’s-eye view down into the minds of the commanders, and then further into the mud and smoke to show the human side of battle from many perspectives. This can easily be seen in the variety of reactions at the Battle of Borodino. Bumbling Pierre, still dressed in civilian garb, is drawn by curiosity to the staging area for the battle (not long after, he would find himself thrust into the heart of the battle, onto the Raevski Redoubt, “la fatale redoute, la redoute du centre, around which tens of thousands fell”). As gangs of wounded soldiers limp back from the front, Pierre observes fresh columns of soldiers in crisp uniforms, with polished weapons, eagerly proceeding to the engagement. They gawk at his nobleman’s white hat, and he is overcome by the thought that “they may die tomorrow; why are they thinking of anything but death? . . . The cavalry ride to battle and meet the wounded and do not for a moment think of what awaits them, but pass by, winking at the wounded. Yet from among these men twenty thousand are doomed to die, and they wonder at my hat! Strange!” The ambitious young officer Boris Drubetskoy coldly mulls over the inevitable shifts of organizational power that will take place in the command echelons of the Russian army, possibly easing the way for his own promotion: “Now the decisive moment of battle had come when Kutuzov would be destroyed and the power pass to Bennigsen, or even if Kutuzov won the battle it would be felt that everything was done by Bennigsen. In any case many great rewards would have to be given for tomorrow’s action, and new men would come to the front. So Boris was full of nervous vivacity all day.”

Dolokhov, a hard-drinking rake and duelist, valiantly offers his services to the Russian general Kutuzov on the eve of battle: “If I were right, I should be rendering a service to my Fatherland for which I am ready to die . . . And should your Serene Highness require a man who will not spare his skin, please think of me . . . Perhaps I may prove useful to your Serene Highness.” Prince Andrew, attached to the highest level of command, becomes disenchanted with the petty jostling and pretensions of the officers and heroically sets off to fight alongside the rank and file. He explains to Pierre:

“If things depended on arrangements made by the staff, I should be there making arrangements, but instead of that I have the honor to serve here in the regiment with these gentlemen, and I consider that on us tomorrow’s battle will depend and not on those others . . . Success never depends, and never will depend, on position, or equipment, or even on numbers, and least of all on position.”

“But on what then?”

“On the feeling that is in me and in him,” he pointed to Timokhin, “and in each soldier.”

This likely reflects Tolstoy’s own belief. It is a direct refutation of Thomas Carlyle’s famous great man theory, the notion that history is made by audacious exploits carried out on the part of a small number of geniuses, such as Napoleon, Julius Caesar, and Alexander the Great. Tolstoy asserts his counter theory quite clearly when explaining the outcome of the Battle of Borodino:

It was not because of Napoleon’s commands that they killed their fellow men. And it was not Napoleon who directed the course of the battle, for none of his orders were executed and during the battle he did not know what was going on before him. So the way in which these people killed one another was not decided by Napoleon’s will but occurred independently of him, in accord with the will of hundreds of thousands of people who took part in the common action. It only seemed to Napoleon that it all took place by his will.

Despite the careful preparations of the great man, the battle assumes a will of its own. Napoleon arrogantly remarks, “The chessmen are set up, the game will begin tomorrow!” To Pierre, caught in the center of the battle the next day, Napoleon’s imagined chess game is little more than bedlam and bloodshed: “A cannon ball struck the very end of the earth work by which he was standing, crumbling down the earth; a black ball flashed before his eyes and at the same instant plumped into something . . . Pierre, having run down from Raevski’s battery a second time, made his way through a gully to Knyazkovo with a crowd of soldiers, reached the dressing station, and seeing blood and hearing cries and groans hurried on, still entangled in the crowds of soldiers.” For the mastermind, Napoleon, viewing from the opposite heights, it is impossible to tell what is actually happening:

Napoleon, standing on the knoll, looked through a field glass, and in its small circlet saw smoke and men, sometimes his own and sometimes Russians, but when he looked again with the naked eye, he could not tell where what he had seen was . . . From the battlefield adjutants he had sent out, and orderlies from his marshals, kept galloping up to Napoleon with reports of the progress of the action, but all these reports were false, both because it was impossible in the heat of battle to say what was happening at any given moment and because many of the adjutants did not go to the actual place of conflict but reported what they had heard from others; and also because while an adjutant was riding more than a mile to Napoleon circumstances changed and the news he brought was already becoming false.

Peace

Even in peace, we discover the denizens of St. Petersburg and Moscow maneuvering to gain an upper hand, to arrange advantageous marriages or undermine ones with poor prospects, to win favor in the last will of a dying relative, to maintain the appearance of prosperity in financial straits. Endless struggle of one sort or another seems to be part of the human condition. In no other novel does the reader encounter so plainly the peculiar similarities between gory battlefields and gala balls. The Duke of Wellington, who triumphed over Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815, wrote in a letter after the war that the “history of a battle is not unlike the history of a ball. Some individuals may recollect all the little events of which the great result is the battle won or lost, but no individual can recollect the order in which, or the exact moment at which, they occurred.” Nowhere else is Wellington’s peculiar analogy more apt than in War and Peace.

Even in peace, we discover the denizens of St. Petersburg and Moscow maneuvering to gain an upper hand, to arrange advantageous marriages or undermine ones with poor prospects, to win favor in the last will of a dying relative, to maintain the appearance of prosperity in financial straits. Endless struggle of one sort or another seems to be part of the human condition. In no other novel does the reader encounter so plainly the peculiar similarities between gory battlefields and gala balls. The Duke of Wellington, who triumphed over Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815, wrote in a letter after the war that the “history of a battle is not unlike the history of a ball. Some individuals may recollect all the little events of which the great result is the battle won or lost, but no individual can recollect the order in which, or the exact moment at which, they occurred.” Nowhere else is Wellington’s peculiar analogy more apt than in War and Peace.

Preparations for an important ball resemble those for a critical military engagement. Just as the rankings and comparative glory of nations are determined on the field of battle, status and glamour are conferred by a successful showing at a party. One senses the gravity of what is at stake from the frantic pace of Natasha Rostova’s wardrobe before the ball where she is to be first introduced to society:

“That’s not the way, that’s not the way, Sonya!” cried Natasha turning her head and clutching with both hands at her hair which the maid who was dressing it had not time to release. “That bow is not right. Come here!”

Sonya sat down and Natasha pinned the ribbon on differently.

“Allow me, Miss! I can’t do it like that,” said the maid who was holding Natasha’s hair.

“Oh, dear! Well then, wait. That’s right, Sonya.”

“Aren’t you ready? It is nearly ten,” came the countess’ voice.

“Directly! Directly! And you, Mamma?”

“I have only my cap to pin on.”

“Don’t do it without me!” called Natasha. “You won’t do it right.”

“But it’s already ten.”

They had decided to be at the ball by half past ten, and Natasha had still to get dressed . . .

The society ball is the field of battle where mothers scheme to position desirable marriages for their daughters with dashing young officers who are, often as not, aware of little beyond their own pleasures of the moment, an evening’s opportunity to swagger about in a fine uniform, joke with friends, and turn lovely young ladies about on the dance floor.

Iogel’s were the most enjoyable balls in Moscow. So said the mothers as they watched their young people executing their newly learned steps, and so said the youths and maidens themselves as they danced till they were ready to drop, and so said the grown-up young men and women who came to these balls with an air of condescension and found them most enjoyable. That year two marriages had come of these balls. The two pretty young Princesses Gorchakov met suitors there and were married and so further increased the fame of these dances.

As on the dance floor, so in government office. In his professional life, Prince Andrew comes to recognize the degree to which civil society, business, and bureaucracy resemble the rivalries of the salon and teeming clashes of the battlefield:

From the irritation of the older men, the curiosity of the uninitiated, the reserve of the initiated, the hurry and preoccupation of everyone, and the innumerable committees and commissions of whose existence he learned every day, he felt that now, in 1809, here in Petersburg a vast civil conflict was in preparation . . .

Throughout the novel, Tolstoy shows humanity’s propensity for conflict. Again, in war and peace, characters struggle to locate paths to happiness through dense thickets of conflict. Nicholas Rostov, the eldest Rostovson, finds that he is comforted by the regularity and simplicity of military life after the frustration and confusion of civilian life. He feels at home with his regiment, the Pavlograd hussars, a unit of fast, light cavalry: “When returning from his leave, Rostovfelt, for the first time, how close was the bond that united him to Denisov and the whole regiment.” He “felt himself deprived of liberty and bound in one narrow, unchanging frame, he experienced the same sense of peace, of moral support, and the same sense of being at home here in his own place, as he had felt under the parental roof.” Still, as reassuring as military life may be for some characters, war itself is always viewed by Tolstoy as a kind of primitive madness, as we discover when Napoleon prepares for war against Russia:

On the twelfth of June, 1812, the forces of Western Europe crossed the Russian frontier and war began, that is, an event took place opposed to human reason and to human nature. Millions of men perpetrated against one another such innumerable crimes, frauds, treacheries, thefts, forgeries, issues of false money, burglaries, incendiarisms, and murders as in whole centuries are not recorded in the annals of all the law courts of the world, but which those who committed them did not at the time regard as being crimes.

Several of the principal characters in the novel undergo a momentous change when faced with bodily harm, extreme privation, and devastating personal loss. Pierrebegins the novel as an aimless, profligate playboy who inherits one of the greatest estates in all of Russia. After Pierre, jealous of his wife Helene’s loose affections, injures the obnoxious Dolohov in a duel, he frantically begins to question his life: “Who is right and who is wrong? No one! But if you are alive—live: tomorrow you’ll die as I might have died an hour ago. And is it worth tormenting oneself, when one has only a moment of life in comparison with eternity?” The characters come to learn that individual motivation and good intentions go only so far. One may make decisions, for better or worse, but only within the larger world in which one lives. Much will be beyond control.

There are two sides to the life of every man, his individual life, which is the more free the more abstract its interests, and his elemental hive life in which he inevitably obeys laws laid down for him.

After many disorienting experiences—surviving a duel, wandering the field at Borodino, an unsuccessful assassination attempt of Napoleon, and being captured by French soldiers in the ruins of Moscow—Pierre becomes a solemn philosopher, prepared to do all he can to help others. Similarly, Natasha changes from a flirtatious, shallow girl to a deeply nurturing mother after a series of humiliating and painful experiences, including her socially devastating, botched elopement with the already-married womanizer Dolokhov (who views it more as an abduction) and the death of her adored fiancé, Prince Andrew, during the retreat from Moscow. By the time she marries Pierre, they are both utterly altered from what they had been only a few years before the historical tragedy of Napoleon’s invasion.

“People speak of misfortunes and sufferings,” remarked Pierre, “but if at this moment I were asked: ‘Would you rather be what you were before you were taken prisoner, or go through all this again?’ then for heaven’s sake let me again have captivity and horseflesh! We imagine that when we are thrown out of our usual ruts all is lost, but it is only then that what is new and good begins. While there is life there is happiness. There is much, much before us. I say this to you,” he added, turning to Natasha.

“Yes, yes,” she said, answering something quite different. “I too should wish nothing but to relive it all from the beginning.”

Far from being ruined, both are strengthened by strife and dispossession.

Though Tolstoy pays much attention to serious matters—the qualities of evil, intricacies of historical understanding—he always makes room for playful jabs of irony. In fact, the novel has many humorous moments, which is one of the reasons why it remains so readable today. For instance, when the Russian diplomat Bilibin writes a seething, sarcastic letter to Prince Andrew, he begins, “Since the day of our brilliant success at Austerlitz . . .” (which was actually an appalling defeat for the Russians) and goes on to discuss Napoleon:

“The enemy of the human race,” as you know, attacks the Prussians. The Prussians are our faithful allies who have only betrayed us three times in three years. We take up their cause, but it turns out that “the enemy of the human race” pays no heed to our fine speeches and in his rude and savage way throws himself on the Prussians without giving them time to finish the parade they had begun, and in two twists of the hand he breaks them to smithereens and installs himself in the palace at Potsdam.

This sort of mockery reflects Tolstoy’s own skepticism about accepted orders of knowledge—political, military, and even scientific—as when Pierre falls ill with “what the doctors termed ‘bilious fever.’ But in spite of the fact that they treated him, bled him and made him swallow drugs—he recovered.” Tolstoy never hesitates to skewer his characters, deflate pretensions, and mock fraudulent ceremoniousness. The foolish Prince Vasili, “famed for his elocution,” is asked to read out an official letter—“a model of ecclesiastical, patriotic eloquence”—from the emperor at an elegant St. Petersburg soiree, the very day the ferocious Battle of Borodino rages far away. Tolstoy tells us that “[Prince Vasili’s] ‘art’ consisted in pouring out the words, quite independently from their meaning, in a loud, resonant voice alternating between a despairing wail and a tender murmur, so that it was wholly a matter of chance whether the wail or the murmur fell on one word or another.” Such comic episodes, dotted amid the grand arc of calamity and redemption, leaven the novel and make it more human.

A Lasting Impact

The present translation is by Englishman Aylmer Maude (1858–1938) and his wife Louise Maude (1855–1939), an Englishwoman born in Moscow. They befriended Tolstoy and visited him at his Yasnaya Polyana estate, where, in 1902, Tolstoy decided that Aylmer would write his biography, Life of Tolstoy. The Maudes translated all of Tolstoy’s works and labored tirelessly to promote his reputation and ideas in the English-speaking world. Although Aylmer devoted himself largely to Tolstoy’s philosophical writings, and Louise to the literary works, they worked as a team on War and Peace. Tolstoy himself insisted that “better translators could not be invented,” and Anthony Briggs, whose translation of War and Peace appeared in 2005, considered them to be the masters. The Maudes’ early twentieth-century translation has stood the test of time, and is still preferred by many readers today.

War and Peace continues to entertain and enliven long after it first entered the world. Tsarist Russia may feel impossibly remote to us at times. Its economic and social institutions were, in fact, drastically different from our own. The societal refinements and customs of its aristocracy are alien to our more relaxed, democratic age. We must use our imaginations to grasp specific class and economic relationships that bind and divide the likes of emperors, aristocrats, and peasants. Still, some things do not change. Tolstoy’s imagined universe of endlessly shifting alliances, romantic infatuations, common deceits, impassioned furies, galling embarrassments, petty rivalries, tender devotions, quiet resentments, fearless sacrifices, and selfless generosities call to us across time. The goodness and evil of the novel’s characters (sometimes of a single character) appeal to us. We understand them and we see ourselves in them. Many concerns of the novel are every bit as familiar in our day as they were in Tolstoy’s or, for that matter, in the turbulent Napoleonic era a half century before that. The questions that keep Pierre awake at night continue to confront us. How does one live a good life? How much should one give of oneself? Can suffering be alleviated, and how? What way to happiness? These questions remain as eternal as the fears, hopes, and loves of Natasha, Prince Andrew, Pierre, and all the other extraordinary creations of Tolstoy’s masterpiece.

1 Comment

It is an internalised philosophical exploration of life. Or so I found it when I first read it at just the most receptive stage of my own life.

Thank you for bringing it all back to me.

Janet